FREE Shipping on all U.S. orders $200+

FREE Shipping on all U.S. orders $200+

Hat Care

The Story Of The Montecristi Hat

September 15, 2017 6 min read

Not a lot of people know the story of where the Montecristi hat originated. To explore that, we travel into the densely forested regions of the Amazon and Ecuador, where a particular breed of low-lying variety of palm trees grow. The leaves of these 'pseudo-palm' trees are where it all started, about 2000 years ago. The legendary Panama hats have been a part of the culture and heritage of the Ecuadorian villages ever since, with the shape and size of the hat changing over the millennia. The pre-Columbian societies of Coaque Jama, Manteña and Chorrera show evidence of a primitive straw hat which looks to be the predecessor of the present form.

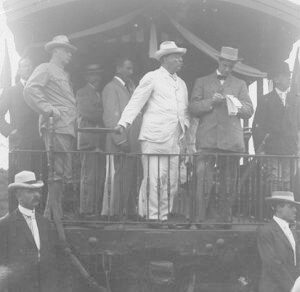

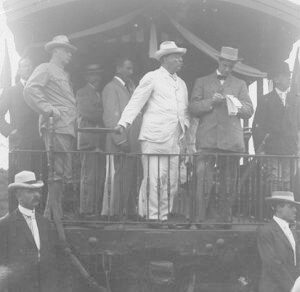

The present form was pieced together a few centuries back, with it being inspired by the Spanish hats with flattened out crowns. Curiously enough, the hat stuck around without any specific name till the early 20th century, when the Panama Canal was being dug. Media attention fell on the little-known country of Panama as people of high stature came to inspect the canal's construction. It included Theodore Roosevelt, the then sitting president of the United States. It so happened that when Roosevelt was there in Panama, he developed a liking towards this obscure hat from Ecuador, produced by artisans from the Ecuadorian province of Manabi (predominantly from the town of Montecristi).

Cameras zoomed in on the president and Roosevelt with his hat became front page news in the US. The rest they say was history. The hat from Ecuador got itself named the Panama Hat, propelling Montecristi-made hats into its rightful stardom that it enjoys till today.

Scenes in Manabi - The Ground-Zero of Panama Hat Weaving

Cameras zoomed in on the president and Roosevelt with his hat became front page news in the US. The rest they say was history. The hat from Ecuador got itself named the Panama Hat, propelling Montecristi-made hats into its rightful stardom that it enjoys till today.

Scenes in Manabi - The Ground-Zero of Panama Hat Weaving

Image credit: AgenciaAndes/CC BY 2.0/Flickr

The province of Manabi is home to some of the best straw hat weavers in Ecuador, especially the ones in the town of Montecristi. But evidently, the sheen of the priceless hats haven't rubbed off on the town itself, with it giving the picture of dusty roads and stilted houses made of wood and bamboo.

The weavers in Montecristi are quite oblivious to the fame that their hats have acquired, with them living simple lives - weaving during dawn and dusk, and helping in the fields during the day. The art of weaving goes back through generations in their family, with most of them learning the trade in their early teens.

Life Cycle of 'Toquilla' - The Straw that becomes the Hat

The straw for the Panama hat comes from large plantations of 'toquilla', which are spread across the coast on the lower slopes of the western cordillera. These plants resemble palm trees, with their stalk-like stems which branch out into fingered bright green leaves. These leaves are the ones that are cut down and dried, later becoming the straw for weaving the hat.

Image credit: AgenciaAndes/CC BY 2.0/Flickr

The province of Manabi is home to some of the best straw hat weavers in Ecuador, especially the ones in the town of Montecristi. But evidently, the sheen of the priceless hats haven't rubbed off on the town itself, with it giving the picture of dusty roads and stilted houses made of wood and bamboo.

The weavers in Montecristi are quite oblivious to the fame that their hats have acquired, with them living simple lives - weaving during dawn and dusk, and helping in the fields during the day. The art of weaving goes back through generations in their family, with most of them learning the trade in their early teens.

Life Cycle of 'Toquilla' - The Straw that becomes the Hat

The straw for the Panama hat comes from large plantations of 'toquilla', which are spread across the coast on the lower slopes of the western cordillera. These plants resemble palm trees, with their stalk-like stems which branch out into fingered bright green leaves. These leaves are the ones that are cut down and dried, later becoming the straw for weaving the hat.

Carludovica Palmata AKA Toquilla palm. Image credit: Dick Culbert/CC BY 2.0/Wikimedia Commons

The selection of the leaves is an art in itself. Care has to be taken that the leaves are of the exact light green hue, meaning that it hasn't phased out in its maturity. Full grown stalks become darker in color and taut with age, which does not suit the weaving process and thus needs to be discarded.

Trained toquilla pickers walk through the plantations every morning, in search of the perfect strands. They make notches in the middle of the stalk and rip out the leaves along the veins, and tie them together with a small piece of stalk. These ribbon-like strands are called the 'cogollos'.

Cogollos aren't themselves the ingredient for weaving. They need to be boiled in earthen pots for about twenty minutes and then dried in the tropical wind, during the breaking dawn and against the setting sun. This is to make sure they aren't exposed to sunlight, which could affect their texture and the retraction process.

Processed cogollos are blond and fine, rolled up inward resembling a cylindrical shaft. At this stage, the damaged and unrefined toquillas are weeded out. The toquillas that remain are then bleached, washed and finally dried to give it the whiteness, suppleness, and fineness of the fiber that is used to weave the Panama Hat. The quality of the Panama hats depend predominantly on the quality of the fiber and thus, Montecristi weavers depend heavily on trusted toquilla pickers to provide them the required strands.

Inside the Weaver's Den - Birth of the Panama Hat

Carludovica Palmata AKA Toquilla palm. Image credit: Dick Culbert/CC BY 2.0/Wikimedia Commons

The selection of the leaves is an art in itself. Care has to be taken that the leaves are of the exact light green hue, meaning that it hasn't phased out in its maturity. Full grown stalks become darker in color and taut with age, which does not suit the weaving process and thus needs to be discarded.

Trained toquilla pickers walk through the plantations every morning, in search of the perfect strands. They make notches in the middle of the stalk and rip out the leaves along the veins, and tie them together with a small piece of stalk. These ribbon-like strands are called the 'cogollos'.

Cogollos aren't themselves the ingredient for weaving. They need to be boiled in earthen pots for about twenty minutes and then dried in the tropical wind, during the breaking dawn and against the setting sun. This is to make sure they aren't exposed to sunlight, which could affect their texture and the retraction process.

Processed cogollos are blond and fine, rolled up inward resembling a cylindrical shaft. At this stage, the damaged and unrefined toquillas are weeded out. The toquillas that remain are then bleached, washed and finally dried to give it the whiteness, suppleness, and fineness of the fiber that is used to weave the Panama Hat. The quality of the Panama hats depend predominantly on the quality of the fiber and thus, Montecristi weavers depend heavily on trusted toquilla pickers to provide them the required strands.

Inside the Weaver's Den - Birth of the Panama Hat

Image credit: hatsfromtheheart/CC BY 4.0/Wikimedia Commons

Montecristi hats require a scale of precision in weaving that is remarkably hard, even to the most skillful of the weavers. It is no surprise hence, that it takes a weaver a better part of six months to finish one Montecristi hat.

The quality of a Panama hat depends on the number of cogollos it takes to make one. A 'fino-fino' of Panama hats has an incredible twenty-eight-row lining, with more than sixty cogollos in them. Making a fino-fino requires prodigious skills and would take more than eight months to finish. A 'fino' hat has fifteen rows with thirty-five cogollos in them, which in itself is tough to weave, usually taking around six months to finish.

A Montecristi is not just known for the complexity of its weaving, but also for the selection of the straw, the fineness of the weave and the regularity of the brim. A finished Montecristi is an exquisite work of art, with its rows arranged neatly in concentric circles of impeccable accuracy. The symmetry of the circles is apparent when the hat is placed under the sun, which signifies the quality of the serried weave.

Making of the 'Ultrafino' Montecristi Hat

Weaving an ultrafino requires patience and perseverance of the highest order. It involves repeating a set of knitting patterns over successive stages. The first step involves the creation of the rosette, which is the center of the crown. It involves a complicated weaving technique with numerous cogollos simultaneously embedded in a tight fitting lattice. Depending on the weaver's dexterity, more strands could be added to the knitting to enlarge the inner circle and to bring the crown to the desired size.

Making the crown is central to the finish of the hat, and since it involves multiple cogollos, straws with high fineness and pliancy are required. The crown is weaved in a seated position after which it is placed on a form which is set on a tripod stand. From here on, the rest of the work is done in an upright weaving position, which is necessary to control the angle of knitting.

The final part of the hat is the brim, which is customized as per the requirement and also the aesthetic eye of the weaver. When the last of the rows are in place, the straws are knotted all around the brim, finishing the hat.

The Dying Art of Montecristi Hat Weaving

Though the Montecristi hats are highly valued in the market, the number of artisans practicing this delicate art is dwindling by the day. In the region of Manabi, a lot of people would claim to know the art, but a very few could achieve the excellence the hats are earmarked for.

The prevailing situation is alarming on many counts. The art of weaving is traditional and lives mostly through generations of familial connections to the trade. With the advent of technology, it is in the danger of vanishing, with the present generation moving out to work on jobs with better financial security. Yet, there have been several localized attempts in Ecuador to revitalize the art. Weaving courses are being introduced to encourage youngsters into practicing the trade. The Banco Central del Ecuador has been awarding young weavers a certificate of aptitude after sixteen hours of training, which it hopes could improve the situation. In the December of 2012, UNESCO recognized the tradition of Panama hat making as an “intangible cultural heritage”, which needs to be protected.

One of the better ways to keep the tradition alive is to make sure the weavers get well compensated for the work they do. Most of the corporate firms that work with the local Ecuadorian weavers tend to exploit their unawareness and pay them a fraction of what their hats go for in the market. Ultrafino is looking to change this, by cutting out middlemen and buying directly from the weavers. This helps in paying the artisans a lot more and in essence, provides support to an art that has been the cornerstone of Montecristi for over two thousand years. Every Panama hat you pick from Ultrafino has a story of sweat and love behind it, and we believe that their stories need to be heard forever after.

Our Montecristi Collection can be found here.

Image credit: hatsfromtheheart/CC BY 4.0/Wikimedia Commons

Montecristi hats require a scale of precision in weaving that is remarkably hard, even to the most skillful of the weavers. It is no surprise hence, that it takes a weaver a better part of six months to finish one Montecristi hat.

The quality of a Panama hat depends on the number of cogollos it takes to make one. A 'fino-fino' of Panama hats has an incredible twenty-eight-row lining, with more than sixty cogollos in them. Making a fino-fino requires prodigious skills and would take more than eight months to finish. A 'fino' hat has fifteen rows with thirty-five cogollos in them, which in itself is tough to weave, usually taking around six months to finish.

A Montecristi is not just known for the complexity of its weaving, but also for the selection of the straw, the fineness of the weave and the regularity of the brim. A finished Montecristi is an exquisite work of art, with its rows arranged neatly in concentric circles of impeccable accuracy. The symmetry of the circles is apparent when the hat is placed under the sun, which signifies the quality of the serried weave.

Making of the 'Ultrafino' Montecristi Hat

Weaving an ultrafino requires patience and perseverance of the highest order. It involves repeating a set of knitting patterns over successive stages. The first step involves the creation of the rosette, which is the center of the crown. It involves a complicated weaving technique with numerous cogollos simultaneously embedded in a tight fitting lattice. Depending on the weaver's dexterity, more strands could be added to the knitting to enlarge the inner circle and to bring the crown to the desired size.

Making the crown is central to the finish of the hat, and since it involves multiple cogollos, straws with high fineness and pliancy are required. The crown is weaved in a seated position after which it is placed on a form which is set on a tripod stand. From here on, the rest of the work is done in an upright weaving position, which is necessary to control the angle of knitting.

The final part of the hat is the brim, which is customized as per the requirement and also the aesthetic eye of the weaver. When the last of the rows are in place, the straws are knotted all around the brim, finishing the hat.

The Dying Art of Montecristi Hat Weaving

Though the Montecristi hats are highly valued in the market, the number of artisans practicing this delicate art is dwindling by the day. In the region of Manabi, a lot of people would claim to know the art, but a very few could achieve the excellence the hats are earmarked for.

The prevailing situation is alarming on many counts. The art of weaving is traditional and lives mostly through generations of familial connections to the trade. With the advent of technology, it is in the danger of vanishing, with the present generation moving out to work on jobs with better financial security. Yet, there have been several localized attempts in Ecuador to revitalize the art. Weaving courses are being introduced to encourage youngsters into practicing the trade. The Banco Central del Ecuador has been awarding young weavers a certificate of aptitude after sixteen hours of training, which it hopes could improve the situation. In the December of 2012, UNESCO recognized the tradition of Panama hat making as an “intangible cultural heritage”, which needs to be protected.

One of the better ways to keep the tradition alive is to make sure the weavers get well compensated for the work they do. Most of the corporate firms that work with the local Ecuadorian weavers tend to exploit their unawareness and pay them a fraction of what their hats go for in the market. Ultrafino is looking to change this, by cutting out middlemen and buying directly from the weavers. This helps in paying the artisans a lot more and in essence, provides support to an art that has been the cornerstone of Montecristi for over two thousand years. Every Panama hat you pick from Ultrafino has a story of sweat and love behind it, and we believe that their stories need to be heard forever after.

Our Montecristi Collection can be found here.

Cameras zoomed in on the president and Roosevelt with his hat became front page news in the US. The rest they say was history. The hat from Ecuador got itself named the Panama Hat, propelling Montecristi-made hats into its rightful stardom that it enjoys till today.

Scenes in Manabi - The Ground-Zero of Panama Hat Weaving

Cameras zoomed in on the president and Roosevelt with his hat became front page news in the US. The rest they say was history. The hat from Ecuador got itself named the Panama Hat, propelling Montecristi-made hats into its rightful stardom that it enjoys till today.

Scenes in Manabi - The Ground-Zero of Panama Hat Weaving

Image credit: AgenciaAndes/CC BY 2.0/Flickr

Image credit: AgenciaAndes/CC BY 2.0/Flickr Carludovica Palmata AKA Toquilla palm. Image credit: Dick Culbert/CC BY 2.0/Wikimedia Commons

Carludovica Palmata AKA Toquilla palm. Image credit: Dick Culbert/CC BY 2.0/Wikimedia Commons Image credit: hatsfromtheheart/CC BY 4.0/Wikimedia Commons

Image credit: hatsfromtheheart/CC BY 4.0/Wikimedia CommonsSubscribe

Sign up to get the latest on sales, new releases and more …